What has business innovation got to do with the challenge of enabling better physical health outcomes for people with psychotic illness?

This was the question being asked at a recent Symposium led by the Psychosis Australia Trust. The answer required a deeper dive into the literature and practice of innovation management, drawing out crucial success factors of business innovation, and spanning the boundaries between economic prosperity and social wellbeing.

The active ingredients of transformative change for effective innovation in business and for solving difficult social problems are similar—a greater focus on human dimensions of business innovation, and not the conventional view that innovation equals technology and scientific research and commercialization.

The following key insights were shared with mental health policy professionals and advocates about the lessons from business innovation:

· Impact, not just ideas

While innovation is more than just technology and research breakthroughs, it is less than just any form of creativity, bold new idea or entrepreneurial flair. Innovations hinge on execution; they must be put into action and make an impact.

Innovation is not an end in itself, but a vehicle for economic and social progress. Therefore, the innovation must also meet a recognized need or gap.

Put simply, innovation is defined as creating value by doing something new, which is needed and useful, and well-executed.

· Learning, not ‘light bulbs’

Vital for putting bold ideas into effective action is the need to enhance innovation capabilities in enterprises, their management and workforces.

Success through new-to-the-world technologies and discoveries is rare. More likely, innovation capabilities are the result of enterprises:

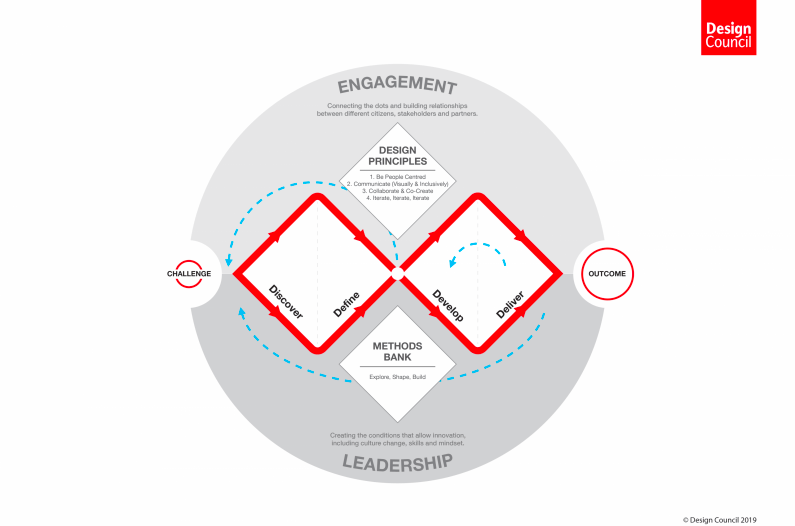

- Learning by doing, through small, rapid and safe experimenting with new ideas in real world situations.

- Learning by using advanced technologies that bring new capabilities, and by mining diverse sources of existing knowledge such as design, market research, licences and prototyping.

- Learning by interacting with others through inter-firm collaboration, personnel movements, links to professional bodies and the like.

Most importantly, performance and productivity gains are realised when these innovative approaches are brought together in a transformed business model, a recipe which creates superior value for customers by meeting an unmet need and earns a premium for the business in doing so.

· Not a solitary pursuit

No single individual or organisation holds all the answers. To get results, innovation practices require investment and contributions from multiple actors, disciplines and sources of knowledge.

Proficiency at collaboration is a significantly powerful innovation capability. Collaboration includes the ability to share information and to learn, to be outward and forward-looking, and to solve problems by cross-fertilisation of knowledge and expertise.

Skill at collaboration is valuable, not just in formal joint ventures and partnerships, but in managing relationships, building trust and shared interests, negotiating diverse opinions and outlooks, and brokering industry clusters, innovation eco-systems and communities of practice.

Similarly, encouraging flows of knowledge, is more important for securing innovation outcomes than just increasing stocks of knowledge held by individuals and organisations. The challenge is balancing the quest for diverse knowledge with efforts to continually strengthen deep, specialist knowledge.

· More about the user than the producer

Any innovation worth doing should solve problems that matter to customers, consumers and communities, rather than being focused on the perspectives and assets of the producer or those tasked with fixing the problem.

A key theme here is the concept of people-led change.

People-led change involves harnessing and acting on the bold ideas for change for the better from a diverse range of perspectives, including from the general public, those directly affected by the problem, and those not usually well-connected to decision makers.

The power lies in unlocking their different insights and sources of knowledge as an untapped source of innovation. Among the approaches to activate people-led change are open innovation, crowd-sourcing projects and design-thinking initiatives.

In summary, this wider, less publicised angle on business innovation recognises many different forms of innovation—incremental, radical, disruptive and focused variously on products, services, processes and transformed business models.

It serves to uncover a broader range of ideas and contributors as change agents to put innovative ideas into action. It shows that innovation is not a rarefied concept, but one that affects the daily lives of ordinary people.

By being human-centred, not technology-based, these fresh insights build a bridge from business innovation experience to new ways of addressing difficult and complex social and community problems that are resistant to easy answers.

REFERENCES:

Based on a presentation on ‘The Power of People-Led Change’ by Narelle Kennedy AM to the Psychosis Australia Trust 2022 Symposium, 15th September 2022.